Implicit Learning, Intuition and Bias

In the last two sections of this lecture I felt it is necessary to raise two more warning tales, precisely because we will work with such a powerful machinery and attempt to tackle complex problems in our jobs and lives.

A good metaphor for what we’re doing in this course is the way people learn. In a way we’re pattern recognition machines, with a powerful capacity for implicit learning, meaning we can’t articulate or explain how we did it. For example, riding a bike, catching a baseball, speaking, reading and writing, behaving in social situations and so on.

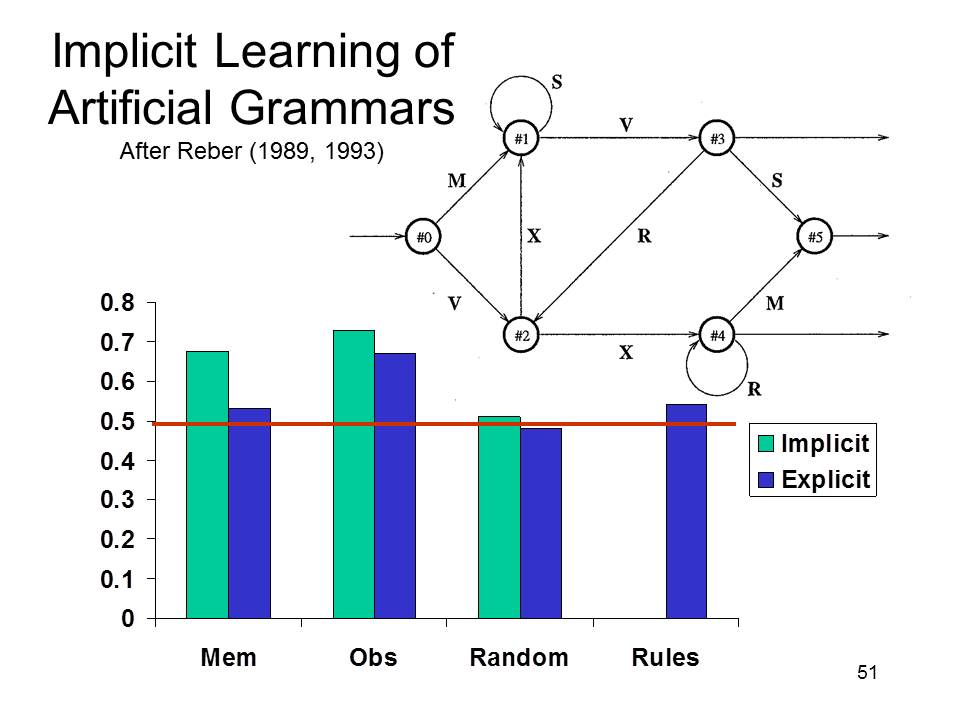

There is a famous experiment, in which researchers invented words from two languages, meaning two set of rules,1 let’s say between 3 and 8 characters, with appropriate vowels and so on. Total gibberish, but here we are, with two sets of words.

Participants saw the lists and they had to say from what “language” does a word come from. It is a good example of experiment design coming from cognitive science research.

1 For the curious, they used a Markov Chain artificial grammar, which would be pretty straightforward to implement in R, and is a way of looking at the language which brought the first breakthroughs in NLP (natural language processing)

Following the experiment, this means that those rules articulated by the people in the experiment were NOT how they were thinking. There is something going on which can’t really be articulated. This means that we have a capacity to find patterns and regularities in the real world, due to evolution building into us this powerful machinery of implicit learning.

Another hypothesis about how animals learn is the idea that some prior 2 knowledge or mechanism – which is there due to evolution optimizing for fittedness, is necessary to kickstart the process. The discussion about the fascinating interaction between nature and nurture is outside the scope of the point I’m trying to make right now. So, here we go with two more experiments:

2 We will go into more technical details when discussing Statistical Learning and ML models, of why is it the case that biasing a learning process with prior information is essential to successful learning.

When rats stumble upon food with new smell or look, they first eat very small amounts. If they got sick, that novel food is likely to be associated with illness, and in the future the rat will avoid it. Quoting Dr. Shai-Ben David:

Clearly, there is a learning mechanism in play here – the animal used past experience with some food to acquire expertise in detecting the safety of this food. If past experience with the food was negatively labeled, the animal predicts that it will also have a negative effect when encountered in the future. 3

3 Shai-Ben David - Understanding Machine Learning, 2014

The bait shyness is an example of learning, not just rote memorization. More exactly of a basic inductive reasoning, or in a more statistical language, of generalization from a sample. But we intuitively know, that when generalizing a pattern, regularity is sometimes error prone: we pick up on noise, spurious correlations instead of signal, we’re fooled by randomness.

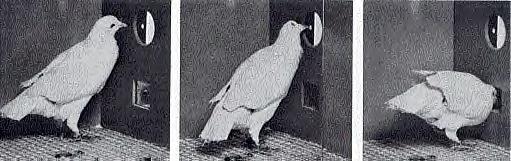

In an experiment, B.F. Skinner put a bunch of hungry pigeons in a cage and gave them food at random intervals via an automated mechanism. They were doing something when the food was first delivered, like turning around or pecking – which reinforced that behavior.

Therefore, they spent more time doing that exact same thing, without regard with the chances of those actions getting them more food. That is a minimal example of superstition, a topic on which philosophers spilled so much ink.

Shai-Ben David goes on to argue – what stands at the foundations of Machine Learning, are carefully formulated principles which will prevent our automated learners, who don’t have a common sense like us, to reach these foolish and superstitious conclusions. 4

What is the common thread among these three stories about learining? In a nutshell, it’s about cultivating the wisdom and ablility to differentiate between correlational and causal patterns.

- When all goes well we call it intelligence, intuition, a business knack. It’s our pattern recognition picking up on some real, causal regularities. It’s the common sense working as it is supposed to.

- When learning goes awry, it’s a bias and in worst cases – bigoted prejudice.

- I am not a fan of how behavioral economics treats biases, 5 but here are a few so prevalent and harmful outside their intended evolutionary purpose, that we have to mention them: confirmation bias, recency, selection, various discounting biases.

- We attribute a causal explanation to a phenomena when it’s not. For example, size of the wedding to a long-lasting marriage, extroversion and attractiveness with competence, how religious are people vs years of life.

- There are numerous examples, and I don’t have to repeat that correlation doesn’t imply causation, due to common causes, hidden variables, mediators, reverse causes and confounders.

5 The reasons come from cutting-edge Cognitive Science research, which challenge the normative position of economic rationality. Moreover, they challenge the economic orthodoxy when it comes to rationality – it is a much more complex beast than a maximisation of expected utility.

So, what can we do as individuals and professionals? I think one way to get wiser is to cultivate a kind of active open-mindedness, which tries to scan for those biases and bring them into our awareness, such that we can correct our beliefs, behavior and decisions. Another thing we can do is to update our beliefs often, in the face of new evidence, keeping a scout mindset, trying to see clearly, instead of getting too attached and invested in our beliefs and positions.

I think we’re extremely lucky to be in a field like data science, where we can use formal tools from probability, causal inference, machine learning, optimization, combined with large amounts of data and domain expertise – in order to practice that kind of a mindset. However, let’s keep in mind how easy researchers are getting fooled, not only by randomness, and that we’ll never be immune to misjudgement.

The same machinery which makes us intelligent general problem solvers and extraordinarily adaptable, makes us prone, vulnerable to bullshit and self-deceptive, self-destructive behavior.

It is the same, in a more techincal sense, with overfitting ML models and drawing wrong inferences. In business settings, I believe that firms will realize and appreciate that a decison scientist has this exact role – to help others rationally pursue their goals and strategy.

Calling Bullshit in the age of Big Data

You probably noticed that I used the word bullshit a few times in this lecture. It is not a pejorative, but a technical/formal term introduced by Harry Frankfurt in his essay “on Bullshit”. In romanian, the closest equivalent would be “vrăjeală”, a kind of sophistry.

A liar functions on respect for the truth, as he inverts parts of a partially true story to convince you of a different conclusion. It is interesting that we can’t really lie to ouselfs, we kind of know it’s a lie – so we do the other, we distract our attention away from it.

In Bullshit, you try to convince someone of something without regard for the truth. You distract their attention, drown them in irrelevant, but supersalient stuff.

In our age, BS is much more sophisticated than the “good old” advertisement trying to manipulate you to buy something. I can’t recommend enough that you watch the lectures by Carl T. Bergstrom and Javin West,6 where they explain at length numerous ways we’re being convinced by bullshit arguments, but which are quantitative and have lots of jargon and pretty charts in them.

6 Carl T. Bergstrom and Javin West - Calling Bullshit: The art of Skepticism in a Data-Driven World

The kind of intimidating jargon comes from finance people, economists, when explaining why interest rates were risen, what happened in 2007-2008 great financial crisis. My “favorite” is cryptocurrency-related sophistry and some particular CEOs expertly making things more ambiguous, mysterious, and complicated with their corporate claptrap.

These lectures are short, fun, informative and useful for developing the critical thinking necessary when assesing the quality of the evidence or reasoning which led to a particular conclusion. I will try to incorporate here and there some examples from their course, where it fits naturally with our use-cases and theoretical topics, especially in causality.

There are tempting arguments which boil down to this: due to ever increasing volumes and richness of data, together with computing power and innovations in AI – it will lead to the end of theory. I couldn’t disagree more!

In huge datasets of clients and web events, there are lots of observations and many features/attributes being collected, which theoretically should be excellent for a powerful ML model.

However, at the level of each observation, when we go to a very granular aggregation level, the information can be extremely sparse, with high cardinality, inconsistent (all data quality issues). For example, in an e-commerce, for a customer, you might have no information about their purchases, and just a few basic facts about their website navigation.

So, you have the cold start problem, data missing not at random, censoring/survival challenges, selection biases. The data at the lowest level becomes discrete, noisy, heteroskedastic. You know the saying: garbage in garbage out.

Even in ML when there is a big, clean and rich dataset, we can’t escape theory (which is our understanding of the world), in one way or anover. For example, in demand forecasting, we need to provide the model relevant data, factors which are related, plausibly influencing that demand: like weather, holidays, promotions, competition, and so on.

We can’t just pour all this data into a ML model and expect the best. It isn’t clear that feeding irrelevant data doesn’t break or bias our model, such that it picks up on noise and spurious correlation, especially in very powerful DL models. That definitely doesn’t help with better decisions. From an engineering standpoint, I recommend you watch this talk “Big Data is Dead” by the creator of DuckDB.

In conclusion, there is no magic to AI, no silver bullet: more data and better models are often necessary, but not sufficient to improve outcomes. We have to ask the right questions. We have to set objectives aligned with business strategy. We have to frame and formulate a problem well, understanding it in its context. We have to collect relevant data, clean it, understand the processes of missingness. If we let AI decide who enters into a quarantine during the pandemic, what it would optimize for? It’s just a machinery combining statistics and optimization.

Therefore, critical thinking becomes that much more important when we have these powerful quantitative tools at out fingerprints. A part of a data scientist’s job is to constrain artificial stupidity (more exactly, foolishness, because it does perfectly fine what you instructed it to do) and making sure we’re solving the right problem (sounds trivial, but ofter we solve the wrong problem, without being aware of it).