Scientific process is all you need

Workflow, Methodology, Research Design

People doing analytics, machine learning, and applied statistics recognize the importance of methodology. They design processes and workflows for their domain of expertise, which helps them solve problems systematically. However, it is confusing for a beginner to see so many of them and decide which one to use for each particular application, as I show in the card below.

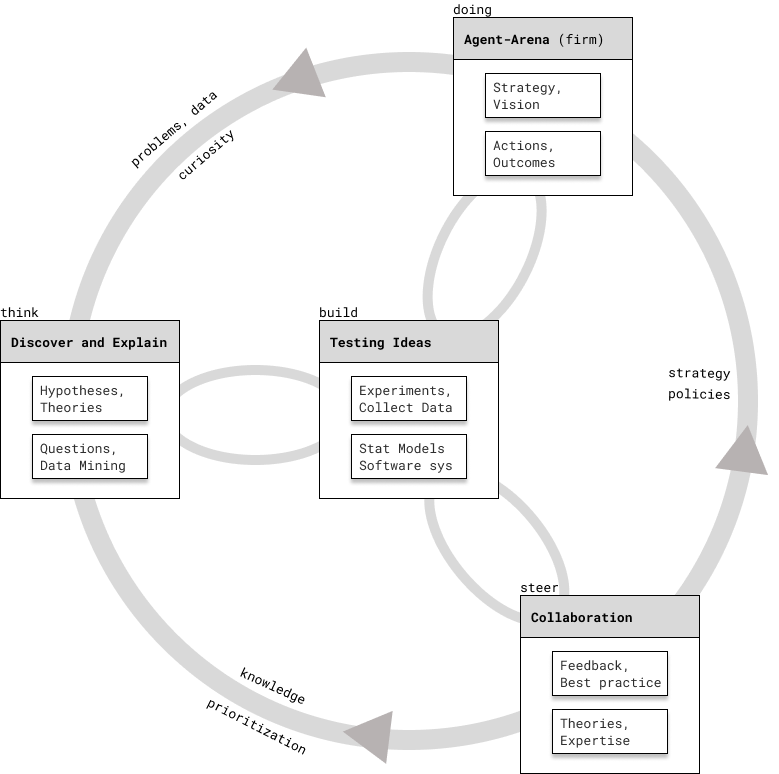

I claim that an adaptation of the scientific process which includes agency, can place each of these processes in its appropriate context and take into account actions and outcomes

For a very long time, I chose a process depending on the type of question and problem at hand. I still do, but I’m increasingly unease about it, as every well-intentioned author seems to make their own slight variations. You know the joke: “I decided to unify 10 existing standards – now we have 11”

Before I explain each box on the diagram1 and how are they connected, I’ll show some processes that you might encounter in literature and practice. Also, think how the scientific process you’re probably familiar with is encompassed by the diagram above: Observations – Hypotheses – Experiment – Data collection – Hypothesis testing – Communicating conclusions.

1 The diagram above is inspired by Berkeley’s “Understanding Science 101”

In data mining, machine learning, and analytics, you might encounter CRISP-DM (cross-industry process for data mining), KDD (knowledge discovery in databases), J. Tuckey’s EDA (exploratory data analysis), A. Fleischhacker’s BAW (business analyst’s workflow), H. Wickham’s tidyverse workflow, and C. Kozyrkov’s 12 steps to AI.

They are heavily focused on pattern recognition, finding inspiration and hypotheses from data (sometimes, in an model-driven way), and building predictive models. Despite their diferences, they all point to the same idea.2

In statistical modeling and experiment design, you might know the stats 101 process for hypothesis testing. More sophisticated workflows are concerned with the whole process of modeling and study design, like C. Kozyrkov’s 12 steps of statistics, A. Gelman’s Bayesian Workflow, R. Alexander’s telling stories with data, and R. McElreath’s simulation-based model development.

All of the above attempt to iteratively develop statistical models (estimators) to answer scientific questions and to gain insight into the underlying causal processes of social science phenomena.

2 Don’t try to memorize them, but go back to this diagram of the scientific process and locate different steps of the workflow.

Out of all these processes, I found C. Kozyrkov’s 12 steps to AI to be extremely useful in predictive applications, 12 steps to statistics in designing A/B tests, and R. McElreath’s process when developing statistical models to draw causal conclusions.

Action and Agent-Arena

First, let’s take the exmple of a firm and think of it as an agent. Hopefully, it has formulated its mission, vision, a strategy to overcome obstacles, and has set reasonable objectives. Employees and leadership of the firm will try to make good decisions and develop capabilities in order to improve performance. At this level of analysis, we don’t need to consider the full implications of a complex adaptive system.

In a happy and lucky case, these actions are coordinated, aligned with strategy and generate desired outcomes. Besides performance, we can also consider an increase in value added brought by improvements in its processes, products, and services.

The firm gathers data about its current and past state \(\{\mathcal{S}_t\}_{1:t}\), observes the environment \(\mathbfcal{O}_t\), its actions \(\mathcal{A}_t\) influence the environment, and vice-versa. It also interacts with other agents in the network, be it customers, suppliers, manufacturers, government, stakeholders, etc.

This perspective is pretty standard in AI research. We can use it to tease out different sources of uncertainty.

I called this element in the scientific process an “agent-arena” relation, because we usually don’t consider the whole firm, but our framing depends on what point of view in the value chain we take. For example, a team responsible for conversion-rate optimization will have its own objectives, decisions, and data they care about \((\mathcal{S}, \mathcal{O}, \mathcal{A} | {POW} )\). Of course, there is a concern of alignment, of local optimization which results in suboptimal global outcomes – but this topic is outside the scope of our course.

In their book Algorithms for Decision Making, MIT Press - 2022, M. Kochenderfer, T. Wheeler, and K. Wray make a helpful classification of the sources of uncertainty, based on agent-environment interactions:

- Outcome uncertainty suggests we can’t know the consequences and effects of our actions with certainty. We can’t take everything into account when making a decision

- Model uncertainty implies we can’t be sure that our understanding, assumptions, and chosen model are correct. In decision-making, we often misframe problems and in statistics, well, choose the wrong model.

- State uncertainty means that the true state of the environment is uncertain, as everything changes and is in flux. This is why statisticians argue that we always work with samples

- Interaction uncertainty due to the behavior of the other agents interacting in the environment. For example, competitive firms, and social network effects.

We will focus very little the last aspect of uncertainty, but you have some tools to reason about it: game-theoretic arguments, ideas from multi-agent systems, and graph theory. I think it is an important dimension of reality, however, taking it into account in this course would make it incomparably more complicated and advanced.

Testing ideas and solutions

At the core of scientific process is experimentation, systematic observation, and testing of ideas – which results in evidence with respect to a hypothesis or theoretical prediction. For our purposes, we consider experimentation in its large sense, not just randomized control trials and highly-controlled experiments.

By including statistical models, simulations, ML models; prototypes, software systems and features – we can benefit from this self-correcting feedback loop not just in science, but in decision-making. For example, leaving aside a test dataset in machine learning is a way to assess and approximate how well a model generalizes beyond training data.

Let’s consider Agile principles and Shape-Up methodology for software development. I think that they fit well into our framework when we’ll sketch out the two remaining pieces

This means that inferential and causal statistical models are equally as important ways to test ideas. Moreover, the ultimate test is whether the recommended decisions based on modeling insights work well in practice. Meaning, we get better outcomes in the agent-arena, our problem space. Let’s see how testing of ideas interacts with other elements in our diagram:

- The insights and recommendations from our experiments inform actions in Agent-Arena. After operationalization, we get feedback on how well it worked and what can we improve

- We have to communicate our insights clearly and persuasively to the people we collaborate with. Our colleague’s expertise will give us best-practices in the field and feedback about the analysis

- With respect to discovery and explanation, we don’t want to test a vague idea, but a well-thought, sharp hypothesis or causal model

The tests will result in stronger or weaker evidence for or against the explanation. We can use simulation to validate that our statistical models work in principle, meaning we recover the estimand (unobservable quantity or effect of interest).

Simulating synthetic data from a causal process model in order to validate if a statistical model can draw correct inferences about the estimand can be considered an experiment, although, one which lives in pure theory, until we apply it to real data. This iterative process lives at the intersection of asking questions, building theories and testing ideas.

Since the data comes from messy real world systems, we will have to consider very carefully how it was collected and measured. This means that when we build models, we might need to learn new tools to correct for biased samples, differential non-response, missing data, measurement error, repeated observations, etc.

For some research questions, measurement and sampling is a complicated problem. This is why I’m trying to integrate them in this course.

Quantitative research methods are a valuable when dealing with the issues outlined above, but are often not part of a statistical curriculum. I highly recommend A. Zand Scholten’s introductory course on Quantitative Methods. It is worth to invest a bit of time to get familiar with the following:

- Measurement is especially relevant and tricky in social science. Sometimes, we do not measure what we think we do. For measuring abstract things like happiness, preferences, or personality – we need to dive into scales, instrumentation, operationalization, validity, and reliability

- Sampling isn’t limited to simple random samples, as these rarely occur in practice. We need to be aware what tools exist so that we can generalize to the population of interest

- Threats to validity, including confounds, artifacts, and biases. On the one hand we use statistics as a guardrail against foolishness, on the other hand there a lot of the same problems that can compromise our study.

Discovery and explanations

One can make a case that wisdom starts in wonder and science with curiosity. Don’t get fooled by statistics classes were hypotheses and theories are taken for granted. Our field has caught up to scientists, in the sense of openness in how we gather inspiration.3

3 Many books have been written about how theories are being developed, the role of curiosity, inspiration, observation, previous theories, and evidence

Model-driven exploratory data analysis an pattern recognition have become acceptable ways to formulate hypotheses. I would argue that for most problems I encountered, this exploratory process was essential. This is precisely the way in which a good analyst is extremely valuable. Note that with this power comes a lot of responsibility to not fall for confirmation bias, hence we’ll need discipline and guardrails.

You will probably agree that asking a good question and formulating / framing a problem well gets us “halfway” towards a solution. We can approach a research design data-first or question-first, but in business practice it’s almost always a mix.

When starting question-first, it’s helpful to think what is the target population of interest, potential interventions, whether we have a comparison group, what are the relevant outcomes, and the time-frame of the study.

Speaking about business decisions, what I mean by theory is our current knowledge and understanding of the problem / domain.4 Don’t get fooled by claims that AI and ML are exempt of theory, assumptions, and will figure out those from data. The mere fact of selecting what to measure and what features to include in the model, involves human understanding and a judgement of relevance.

4 For example, customer preferences and behavior, drivers of the demand, and sourcing of raw materials

In the course we will try our best to ensure that statistical models are answering the right quantitative question, which we call an estimand. It might not be obvious why we worry about the underlying, unobservable, theoretical constructs and ways we could measure them. After all, we’re not doing quantitative psychology.

In my experience, these constructs appear implicitly, for example: willingness to pay, customer satisfaction, engagement, brand loyalty and awareness, who can be convinced to buy via promotions, email fatigure, etc. Hence, the decisions we make in operationalizing these abstract concepts are critical to a project’s success.

Steering and collaboration

Modern research and science in general do not happen in isolation. The same is true in firms and almost any other domain. I will not spill much ink in trying to convince you of the power of collaboration, since almost any problem which is complex enough can’t be tackled by a single individual.5

5 This argument is developed much further in C. Hidalgo’s book “Why information grows” and his research into measures of economic complexity

In the context of this course, we’re thinking of collaboration with clients, stakeholders, experts, engineers, and decision-makers. A few outcomes of this collaboration are the strategy we mentioned at the beginning, policies, interventions, best-practices, feedback, and review. Collaboration informs what should we do, prioritize, build and test, and hypothesise / think about.

I can’t emphasize enough the importance of developing your writing skills. It is both a way of thinking, problem-solving, and communicating ideas. When it comes to academic writing, the structure of a scientific paper is very helpful even in businesses, as it forces you to articulate the relevance of your research, results, and contribution.

Last, but not least, reproducible research and literate programming has become a de-facto standard in the data science world. It is a very important aspect to keep in mind, as your work should be easily checked and reproduced by others if you expect a contribution from them. We have amazing tools for that right now, but it’s still not easy to achieve end-to-end reproducibility and automation.

Particular processes

Now that you have this very general version of the scientific process in your conceptual toolbox, we can look at some particular workflows, see how they map onto it, and what can we learn from them.

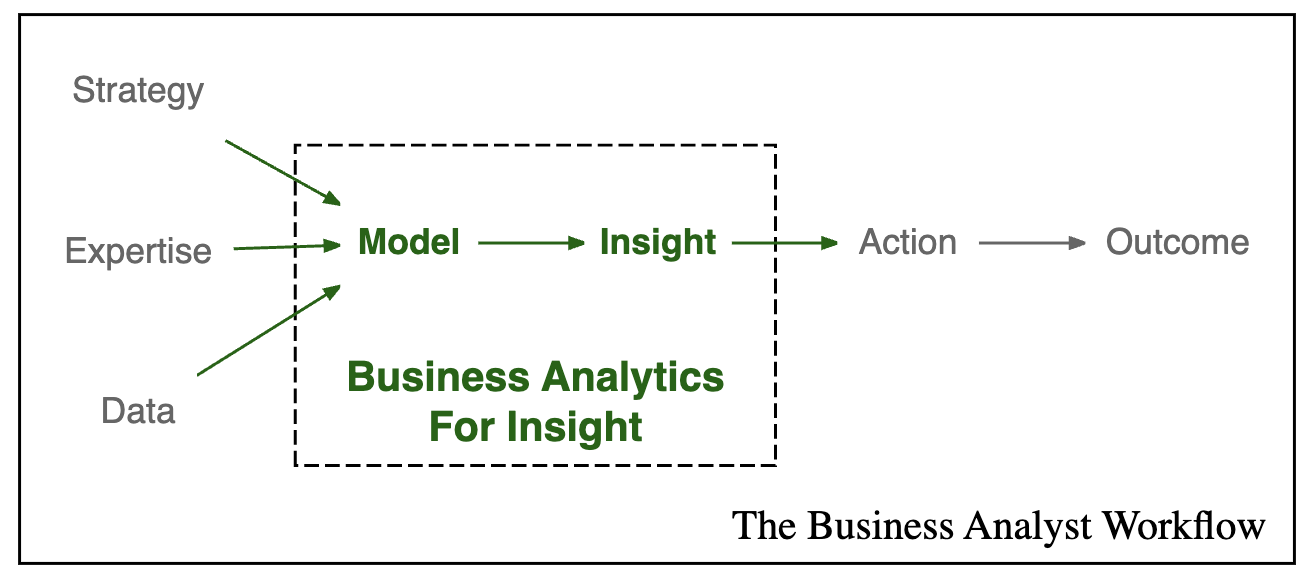

I really like the idea of “Business analyst’s workflow” from A. Fleischhacker 6, which served as a major inspiration for this chapter. The normative criteria for such a workflow are very well aligned with our “project”: it should focus on outcomes, be strategically-aligned, action-oriented, and computationally rigorous.

“You will translate real-world scenarios into both mathematical and computational representations that yield actionable insight. You will then take that insight back to the real-world to persuade stakeholders to alter and improve their real-world decisions.”

12 Steps to Applied AI

Moving on to machine learning and predictive applications, out of all the workflows, I prefer C. Kozyrkov’s “12 steps to applied AI”. It encompasses all others and gives a set of concrete steps when defining and planning for a ML use-case.7 This short reading will dramatically increase your chances to make your predictive use-case successful.

7 Cassie Kozyrkov has a set of lectures for complete beginners which I highly recommend: “Making friends with machine learning”.

First, we need to make sure that ML is the right approach for the problem and that our project is feasible: is there a pattern and do we have relevant data? Then, we need to define our objectives, decisions, constraints and assess how costly is each type of mistaken prediction.

In the second phase, we need to collect data and leave aside a test dataset, so we can check if our model generalizes before we launch it in production. Otherwise, we won’t know if the model is reliable on unseen data. Next, explore the data, clean it up, choose the models you’re going to try, and train them. You might need to debug, iterate, and tune your model pipeline to solve the problems which will inevitably arise.

In the third phase, you have to validate your models, pick the most promising one and test it on the pristine test dataset which was left aside. If the performance is good enough and the model survived our critiques and ways to break it, we’re ready to operationalize and build it for production. Often, we’ll have to run live tests and randomized experiments in order to see if it actually works in practice and it’s safe to launch. At last, we’ll have to monitor its performance, fix bugs, re-train, and maintain the system.

Coming back to our scientific process, you see how these 12 steps have a component of problem formulation, exploration, experimentation, and testing in production. The latter is a ultimate test if our idea (ML use-case) works. We’ll have to improve it based on the feedback we get, then test again.

12 Steps of Statistics

In order to show how this workflow is applied in experiment design, think of an A/B test for improving conversion-rate on a website, a randomized trial which evaluates a new treatment, a quality control sample, or a survey for the next parlamentary election. All of them try to answer a research question.8

8 The relationship between the scientific process and statistical methods has been well explored and established

Before jumping into hypothesis testing, we should ask whether we need an experiment at all. Maybe we want to explore, predict, or we already have access to the whole population of interest (e.g. our customer base)? Or maybe we’re limited to work with observational data and self-reports due to experiments being unethical or unfeasible.

In the frequentist, Neyman-Pearson school of statistical thought, we have to first define our default action, i.e. what would we do in the absence of evidence. When it comes to knowledge, hypotheses, or beliefs – think of acting as if that claim was true. Then, statistics can tell us how to change our actions in the face of evidence, so we’re not wrong too often in the long run. Really strong evidece resulting from a well-designed study and modeling will make our default action ridiculous and unreasonable.

Of course, we have to choose our target population of interest, as our conclusions do not apply beyond it without a strong justification. We also have to define our causal and real-world assumptions and a really good way to do that is by drawing causal diagrams (DAGs). This is where we’ll have to worry about potential threats to validity.

In operationalization, we’ll have to make our research question really sharp and specific, define procedures of how are we going to measure the observable quantities and outcomes of interest, choose the appropriate interventions. As a part of research design, we have to define our data collection strategy and procedures, for which we have to account in the modeling stage.

R. Crump gives an excellent overview of the threats to validity in Chapter 1 of his “Answering questions with data”. Here are some good readings regarding threats to validity in A/B testing:

- “Simple and Complete Guide to A/B Testing” by K. Tatev

- “Avoid the pitfalls of A/B testing” by I. Bojinov

- “8 common pitfalls of running A/B tests” and “An A/B Test Loses Its Luster If A/A Tests Fail” by L. Ye

- On user interference by S. Kumar

One of the most difficult aspects in practice is measurement and metric design. A useful way to think about properties of good metrics is described in this paper by S. Gupta and W. Machmouchi. The STEDII acronym stands for sensitivity, trustworthiness, efficiency, debuggability, interpretability (actionability), and inclusivity (fairness). Here’s another article by A. Rustgi which discusses most common mistakes.

The null and alternative hypotheses tell under what conditions we’ll choose the default or alternative action. At this point, we have all the information needed for us to choose or build the appropriate model or method and validate it on a simulation study. This exercise will tell us if our approach works in principle and in what ways could it fail, especially when our assumptions don’t hold.9

9 It is quite common that our statistical models don’t answer the question we think they do. This is due to poor design and is often jokingly referred to as a “type 3 error” or “the art of solving the wrong problem”

In power analysis, we’ll define our type 1 and type 2 errors, the minimum effect sizes of interest, and figure out how many observations we need for our study to answer the research question.

Notice how much preparation we have to do before we actually collect the data, analyze it, and apply a model or statistical test. This is not because I want rigor for rigor’s sake, but missing a single aspect outlined above in preparation can render our expensive study useless.

Finally, we can start collecting data, launch the experiment and apply the statistical model we defined before. If we did everything right, there is not much work left to do, besides loading and conforming the data to the specification, reporting and communicating our findings.