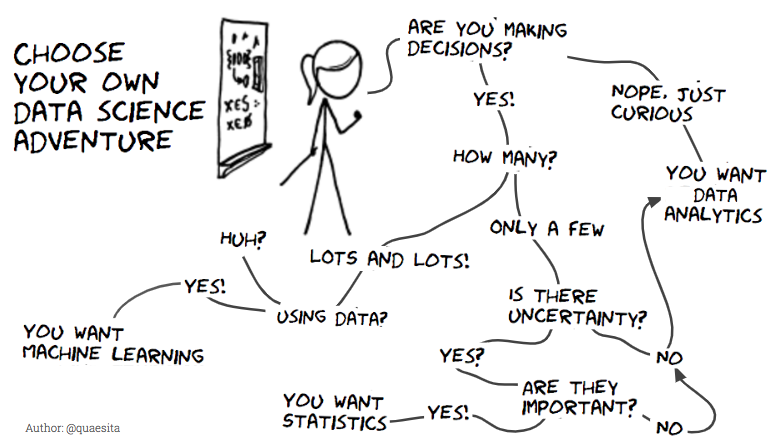

What approach to take?

Analytics, Statistical Modeling, Machine Learning

In decision science, we have a lot of quantitative tools at our disposal, but we should have the wisdom to know which one is appropriate for each applied problem. Of course, it’s foolish to use machine learning when all we need is a controlled experiment or a statistical model which quantifies a causal effect. The converse is also true, you probably won’t use a linear regression to do demand forecasting at scale.

This might sound obvious, however, a surprisingly large number of people fall into the pitfall of misusing ML, or trying to do hypothesis testing when what’s needed is to find inspiration and come up with hypotheses. Even if you could use some ideas from LLMs (large language models) for time series forecasting, it’s often a bad idea.1

1 This is just one of the recent review papers which benchemarked these kind of models and found that they’re no better than well-established approaches

This is not a debate which tools are better, as the question makes no sense – each model has its purpose. Moreover, a statistical model can be used to make predictions, and machine learning methods are heavily used in analytics. For example, statistical models like GLMMs, used without a strong justification from causal inference, quantify only associations – which will result implicitly in doing “analytics”.2

2 Be careful, as lots of research carefully claims only associations, but then treats the conclusions as causal, resulting in policy-making recommendations

As a though experiment, imagine we have an equation or program with well-defined rules, which perfectly predicts the price of stock markets, or how many items will a client buy and how she will respond if we change the price (an intervention). We won’t need machine learning or causal inference.

Of course, we don’t have that kind of program. It’s only somewhat true in cases when we have a well-tested theory, which stood the test of time and went through the scientific process to become the best theory with respect to all others. For example, Newtonian physics, relativity, quantum mechanics, and evolution.

Another good example is accounting, where we have well defined rules (GAAP) for revenue recognition. There is no wiggle-room for ML or stats.

Now, you will be much more careful when people ask you “Can we use AI for that?” Remember, that our starting point is the problem and we choose the appropriate tool, not the other way around.

Analytics and data mining

In analytics, the main goal is formulating better research questions and hypotheses, to get inspiration, find interesting, relevant patterns and relationships in massive datasets. These hypotheses might very well come from experience, observation, domain expertise, qualitative research, or even anecdotal evidence. However, in modern businesses they increasingly come from automated data mining methods and model-driven exploration.3

3 First, it’s more efficient in very unclear situations and second, we can find patterns we couldn’t think of apriori

You should be suspicious, as those hypotheses might not be true and the relationships spurious – they have to be tested in the context of a study or experiment! The mere fact of statistical significance shouldn’t tell you anything at this point, as there are too many potential ways in which our model might not be valid.

Even when you monitor the current state of the business and its performance in a dashboard, which are supposed to be hard facts (given a correct data collection and processing pipeline) – you don’t know yet the reasons and causes of it.4 The same problem appears when we do a survey, if we don’t take into account how data came to be (the reasons for non-response and why our sample is different from population). Therefore, even a good description requires causal and statistical thinking.

4 Reporting these “hard facts” is important, but almost immediately any business person will ask you “Why” and “What should we do about it?”

In many introductory statistics courses, we take the hypothesis for granted, it’s often our starting point. Even worse, the standard textbooks often fail to differentiate between a business / scientific question, a process model, and a statistical hypothesis. They coincide only in the most trivial cases.

There is a combinatorially explosive number of hypotheses we could investigate, so how do we come up with one that is relevant to the outcomes, makes sense, is reasonable, plausible, deserves serious consideration?

I argue it is an art which requires experience and knowledge in a domain, an intuition, sensibility, and attunement to the problem. In my opinion, it is the most underrated aspect of scientific enquiry and process.

In this course we focus on data mining and analytics as a way to get inspiration for good questions to ask and hypotheses to formulate. However, in anthropology or evolutionary biology, it could be done by careful observation of behavior, coupled with a deep understanding of the field, existing theories, their shortcomings and inconsistencies.5

5 Often, these predictions and hypotheses follow from the theory itself

Now, being aware of the potential pitfalls, we can use these insights to select the most promising candidate hypotheses and questions to investigate further. This is one aspect in which an analyst is extremely important, as we can’t afford to test most ideas, nor do we have the time for it. Inspiration is not only useful with respect to questions, but for what features to include in our machine learning models (proxies for the strongest drivers of an outcome).

Statistical modeling

If we have to make a few, high-stakes decisions under uncertainty which have major consequences on business outcomes and user experience, we probably need to do some rigorous statistics. For example, how to price products, to enter a new market or not, what products to develop, how to allocate advertisement spending across different platforms, whether to deploy a new recommender system.

This is an appropriate moment to remember and review the three challenges in statistics, 12 steps when we apply it to a research question, and the array of methodological issues we have to worry about.

We have to decide whether we need to do a randomized controlled trial, a quasi-experiment, or we’re limited to working with observational data, surveys, and self-reports. In contrast with analytics, where we engage in pattern mining, and with machine learning, where we want reliable out-of-sample predictions – in statistics, we need to think very carefully about the causal processes and the assumptions we’re making. Only then we have a chance to give trustworthy recommendations on how to intervene in a system.6

6 Thus, when I say “statistics”, I mean statistical modeling informed by the causal processes and methodological aspects like measurement, samplig, validity, and reliability

Since we deal with human behavior in the value chain of a firm, be it customers, employees, decision-makers, engineers – we need to be aware of the multiple subtle threats to the validity of our study. This means lots of planning and preparation. Moreover, we need to put in a tremendous amount of effort to criticize and validate our model so we can trust its conclusions.

Perhaps, the most common mistake is when people use a predictive, machine learning approach for developing policies and interventions. More exactly, they train a machine learning model on past data and then try out different inputs for the decision variables and pick the ones which maximize an objective. This assumes that the system remains the same, therefore that the learned probabilistic relationship between inputs \(X\) and target \(y\) is unchanged under an intervention.7

7 Perhaps, the clearest explanation of this phenomenon can be found in M. Faucre’s book “Causal inference for the brave and true”, in the chapter “When prediction fails”

Machine learning

If we have to make lots of decisions at scale to optimize a process, for example, demand planning and inventory management for 100k product SKUs, it cannot be done manually or with carefully designed experiments. In this case, an appropriate choice would be to learn from data.

Notice how inventory optimization is a downstream task to the demand forecasting, therefore we’re ok with robust and reliable predictions from a black-box model. A big advantage is if we can also accuratey quantify the uncertainty in those predictions. We still have to be very careful in designing the objective the model is optimizing for,8 what features do we include in the model, and whether they’re drivers or reliable predictors of the demand.

8 A hard problem in machine learning is to make sure the model performance metrics, and maybe loss function is aligned to business objectives. Your colleagues do not care about RMSE and cross-entropy

Why machine learning then, since we put so much emphasis on scientific rigor and trying to infer the causal processes? Sometimes, you just don’t have a theory or process model. For example, in recommender systems it’s just too complicated, with so many heterogenous users and items, each with their specific preferences and idiosyncracies. Then, we take down our scientist lab coat, put on the engineer’s hard hat, and build pragmatic solutions to decision-making at scale.

Machine learning is “simply” a way to use optimization algorithms to go automatically from experience (data) to expertise (a program or recipe for prediction). In other words, models which learn from data find patterns and invariants which generalize beyond the training data.

The next two questions are tremendously important and will prevent you from embarking on an ML project which is doomed from the start:

- Is there an underlying pattern to be discovered?9

- Do I have the necessary and relevant data at training / prediction time?

If yes and yes, we might be in business, but we shall not forget about the pragmatic aspects: is it feasible to be done with a small team, without a huge investment? Are we solving the right problem?

9 Think of a perfectly efficient financial market, there is no pattern to be learned. The same is true for absurd “research” which tries to predict crime propensity or sexuality based on photos.

Don’t get me wrong, there are lots of exciting ML applications, but it’s not a silver bullet and there are numerous pitfalls one fall into. Thus, we should be aware of its power and usefulness, but also limitations. As a recent example, W.Heaven argues that Hundreds of AI tools have been built to catch covid and none of them helped.

One part of the problem is the mismatch between the real world, business problem and objectives, versus what models optimize for. Vincent Warmerdam brilliantly explains it in his talks “The profession of solving the wrong problem” and “How to constrain artificial stupidity”. 10 This should remind you of the conversation about statistical golemns which we had in the course introduction.

10 V. Warmerdam - The profession of solving the wrong problem and How to Constrain Artificial Stupidity

Since we’re engaging in the business of data mining and analytics at one point or another of the project, we have to be extra careful. Intuitively, you understand that discovering hypotheses and testing them on the same set of data is a bad idea, because we’ll get an overly confident estimation of how much evidence we have.

Sometimes, we’ll do exploratory data analysis, find relevant and predictive features for our target variable by trying out a few models on the whole dataset. Next day, we “forget” about this, having the conclusions crystalized in our mind, and apply a new, final model … on the same data.11

Maybe you’ll be lucky and get away with this, but the data is “contaminated” with our mining. Thus, before you get into the nuances of model building, validation, and selection – get into the habit of always splitting your data.

Give that test dataset to a friend, locked under a key and don’t let them give you that data until you have your final model to be deployed and tested.

11 Other times, people accidentally use some information from the test dataset when transforming their variables, e.g. by centering and using the mean on the whole dataset. Or they might use information from the future in a time-series application

At last, we have to go to similar lengths to validate and test our ML model as we did in statistics. You should build guardrails and sanity-checks for different scenarios in which the model might go really wrong. If it passes this rigorous critique, it has greater chance of finding a real pattern and generalize to examples outside our sample.

Implicit Learning, Intuition, and Bias

In the last two sections, I felt it was necessary to raise warning tales about what can go wrong in statistics and machine learning. It’s precisely because we will work with such a powerful machinery and attempt to tackle complex problems in our jobs and lives.

A good metaphor for what we’re doing in this course is the way people learn. In a sense, we’re pattern recognition “machines”, with a powerful capacity for implicit learning. Implicit means we can’t articulate or explain how we did it. For example, riding a bike, catching a baseball, speaking, reading and writing, behaving in social situations, and so on.

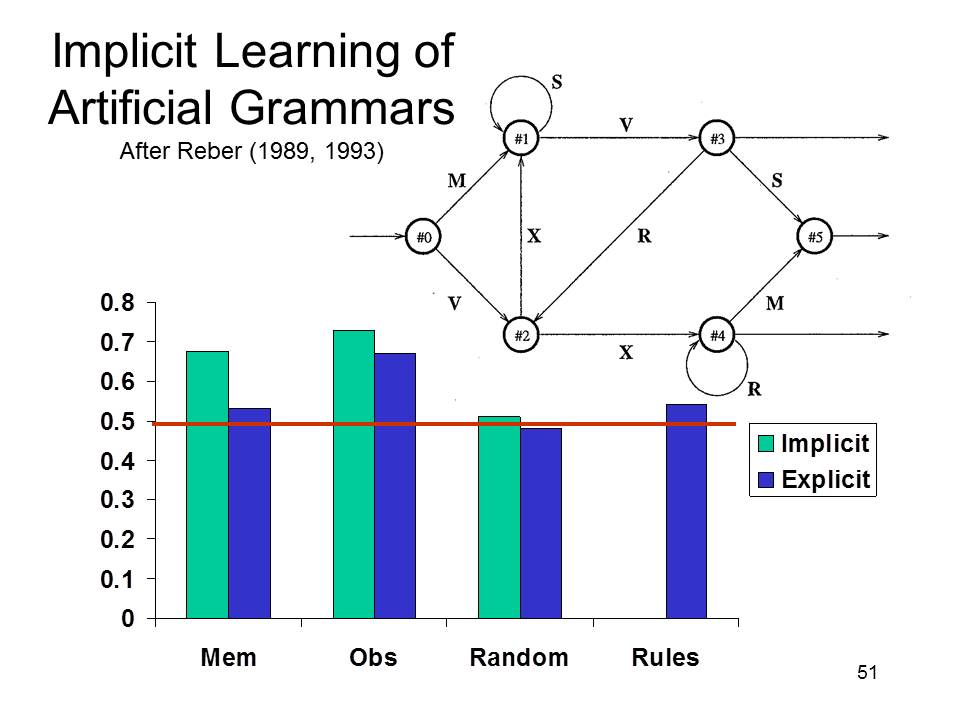

There is a famous experiment, in which researchers invented words from two fake languages, i.e. two set of rules.12 Let’s say the words have between 3 and 8 characters, with appropriate vowel patterns. So, here we are, with two sets of words ready to be shown to our subjects.

Participants saw the lists and they had to say from what “language” does a word come from. It is a good example of experiment design coming from cognitive science research.

They found that subjects differentiated them much better than chance and the results were statistically significant. During the interviews, when asked to explain how they did it, the responses were either “no idea”, or giving some rules. When implemented on a computer, those rules were not able to perform better than a coin flip.

12 For the curious, they used a Markov Chain artificial grammar

In the artificial grammars experiment, those rules articulated by the people were a post-hoc justification and not how they were thinking. Even more surprising is the ability to distinguish between words which are total gibberish. This means we have a powerful capacity to find patterns and regularities in the real world, due to evolution building into us this powerful machinery of implicit learning.

Another hypothesis on how animals learn is the idea that some prior knowledge or mechanism is necessary to kickstart the process. Those mechanisms are there due to evolution optimizing for fittedness. We might refer to them as “instincts” or “natural intuitions”. The discussion about the fascinating interaction between nature and nurture is outside the scope of the point I’m trying to make right now. So, here we go with two more experiments.

When rats stumble upon food with new smell or look, they first eat very small amounts. If they got sick, that novel food is likely to be associated with illness, and in the future the rat will avoid it. Quoting Dr. Shai-Ben David:

“Clearly, there is a learning mechanism in play here – the animal used past experience with some food to acquire expertise in detecting the safety of this food. If past experience with the food was negatively labeled, the animal predicts that it will also have a negative effect when encountered in the future.” 13

13 Shai Ben-David - Understanding Machine Learning, 2014. This book is difficult, mathematical, but highly rewarding if you want to understand the theoretical foundations of ML

The bait shyness is an example of learning, not just rote memorization. More precisely, a basic form of inductive reasoning, or in a more statistical language – generalization from a sample. However, we do know intuitively that generalization is prone to error, as we might pick up on noise and spurious correlation instead of signal – we can get fooled by randomness and mistake it for a real pattern.

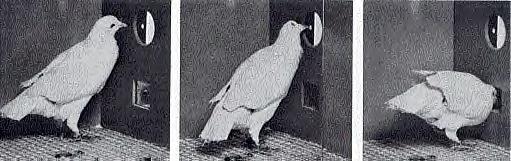

In an experiment, B.F. Skinner put a bunch of hungry pigeons in a cage and gave them food at random intervals with an automated mechanism.14 They were doing something when the food was first delivered, like turning around or pecking. The reward in terms of food reinforced that behavior.

Therefore, they spent more time doing that exact same thing, without regard to the chances of those actions getting them more food. This is an example of superstition, a topic on which philosophers spilled so much ink.

Shai Ben-David goes on to argue – what stands at the foundations of machine learning, are carefully formulated principles which will prevent our automated learners, who don’t have a common sense like us, to reach these foolish and superstitious conclusions.

What is the common thread among these three stories about learining? In a nutshell, it’s about the ablility to differentiate between correlational and real, causal patterns.

- When all goes well we call it intelligence, intuition, a business knack. It’s our pattern recognition picking up on some real, causal regularities. It’s the common sense working as it is supposed

- When learning goes awry, we call it a (cognitive) bias. In worst cases, it can become a bigoted prejudice. We might attribute a causal explanation to a phenomena when it’s not. 15

- You know very well that correlation doesn’t imply causation, due to multiple of threats to validity, including but not limited to: confounders, mediators, colliders, and reverse causalities

15 For example, size of the wedding / long-lasting marriage, extraversion and attractiveness / competence, how religious people are / their ethical behavior

So, what can we do as individuals and professionals? I think one way to get wiser is to cultivate a kind of active open-mindedness, which tries to scan for those biases and bring them into our awareness, such that we can correct our beliefs, behavior, and decisions. Another thing we can do is to update our beliefs in the face of new evidence, keeping a scout mindset, trying to see clearly, instead of getting too attached and invested in our beliefs and positions.

There are a few biases so prevalent and harmful outside their intended evolutionary purpose, that we have to mention them: confirmation bias, recency bias, selection bias, various discounting biases, and survivorship bias.

However, I’m not a big fan of how behavioral economics treats biases. First, if you take the axiomatic economic rationality of expectation maximization to be the normative standard – of course you’ll view any deviation as a bias. It makes no scientific sense to have lists of hundred of biases. At the very least we need a hierarchy, a structural-functional organization of them. Also we need to know their causes!

The best theory we got, in my opinion, comes from 4E Cognitive Science research. First, it challenges the normative position of economic rationality in real-world complexity, ambiguity, and our limited computational resources. Second, it gives us insight into why are we prone to foolishness.

I think we’re extremely lucky to be in a field like decision science, where we can use formal tools from probability, causal inference, machine learning, optimization, combined with large amounts of data and domain expertise – in order to practice that kind of a mindset. However, let’s keep in mind that researchers are not immune to getting fooled.16

16 I think we’re as vunerable as the next person, especially when it comes to decisions outside of our profession

“And with no false modesty my intuition is no better. But I have learned to solve these problems by cold, hard, ruthless application of conditional probability. There’s no need to be clever when you can be ruthless.” – Richard McElreath, Statistical Rethinking

The same machinery which makes us intelligent general problem solvers and extraordinarily adaptable, makes us prone, vulnerable to bullshit and self-deceptive, self-destructive behavior.

By analogy, but in a more technical sense, think of overfitting ML models and drawing wrong inferences. In business settings, I believe that firms will realize and appreciate that a decison scientist has this exact role – to help others rationally pursue their goals and strategy.

Calling Bullshit in the age of Big Data

You probably noticed that I used or implied the word bullshit a few times before. It is not a pejorative, but a formal term introduced by Harry Frankfurt in his essay “on Bullshit”. In romanian, the closest equivalent would be “vrăjeală”, a kind of sophistry.

A liar functions with respect for the truth, as he inverts parts of a true story to convince you of a different conclusion. It is interesting that we can’t really lie to ouselfs, we kind of always know it’s a lie. Thus, we distract our attention away from it with salient, but irrelevant stuff and justifications.

In Bullshit, you try to convince someone of something without regard for the truth. You distract their attention, drown them in irrelevant, but appealing (supersalient) stuff. This is how advertisement works.

In our times, BS is much more sophisticated than the “good old” advertisement trying to manipulate you into buying something. I can’t recommend enough that you watch the lectures by Carl T. Bergstrom and Javin West,17 where they explain at length numerous ways we’re being convinced by bullshit arguments, but which are quantitative, have lots of jargon and pretty charts in them. These lectures are short, fun, informative, and useful for developing the critical thinking necessary when assesing the quality of evidence or reasoning.

17 Carl T. Bergstrom and Javin West - Calling Bullshit: The art of Skepticism in a Data-Driven World

This kind of intimidating jargon comes from finance people, economists, when explaining why interest rates were risen, what happened in 2007-2008 great financial crisis. My “favorite” is cryptocurrency-related sophistry and some particular CEOs expertly making things more ambiguous, mysterious, and complicated with their corporate claptrap.

The last argument I want to address in this chapter is the following: “Due to ever increasing volumes and richness of data, together with computing power and innovations in AI – it will lead to the end of theory”.18 I couldn’t disagree more, both from a philosophical, statistical, and cognitive science perspective.

18 Meaning, you will feed the machines all the data and it will figure out the theories and causal processes by itself, given the right feedback mechanisms

In huge datasets of customer behavior and web events, there are lots of observations and many features / attributes being collected, which theoretically should be excellent for a powerful ML model.

However, when we go to a very granular aggregation level, the information can be extremely sparse, with high cardinality, ambiguous and inconsistent (all data quality issues). For example, in an e-commerce, you might have no information about a user’s purchases, just a few basic facts about their website navigation in the current session.19

Thus, you have deal with the cold start problem, data missing not at random, censoring and survival, selection biases. The data becomes discrete, noisy, heteroskedastic. You know the saying when it comes to machine learning – garbage in garbage out, and no one proved this wrong yet.

19 From an engineering standpoint, I recommend you watch this talk “Big Data is Dead” by the creator of DuckDB.

You can guess the second part of my rebuttal, which reduces to the fact that the causes are not in data. Even when there is a big, clean, and rich dataset, we can’t escape theory, which is our understanding of the world works and how data came to be. Implicitly or explicitly, we’re making an assumption somewhere: what data to include in the model and what is our desired objective.

For example, in demand forecasting, we need to provide the model relevant data about factors and drivers plausibly influencing demand: like weather, holidays, promotions, competition, and so on. First, we can’t collect “all the data” and by including irrelevant stuff we risk picking up on noise and spurious correlations.

In conclusion, AI is not a silver bullet, nor there is any magic to it. More high-quality data and better models are often necessary, but not sufficient to improve outcomes. We have to ask the right questions, frame and formulate a problem well, set objectives aligned with business strategy. If we let AI decide who enters quarantine during the pandemic, what would it optimize for and what unexpected side-effects can those decisions lead to?20 Therefore, a part of a decision scientist’s job is to constrain artificial stupidity. More precisely, foolishness, because it does perfectly fine what you instructed it to do.

20 Remember, we can’t take everything into account, as this problem is combinatorially explosive and computationally unfeasible.